|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

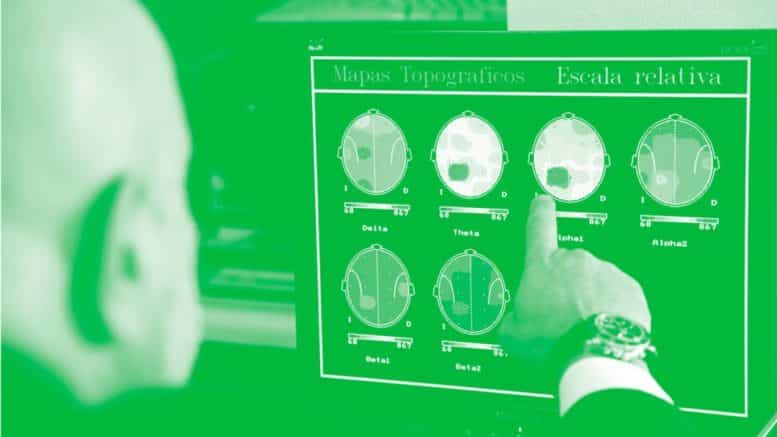

Neuroscience is racing ahead of people's ability to comprehend what it is doing to them. Your simple pictures that exist everywhere these days can produce an emotional profile that can then be manipulated in order to change your mind on an issue. What if the AI give a false analysis and bad data gets stamped into your profile record? Too bad.