|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

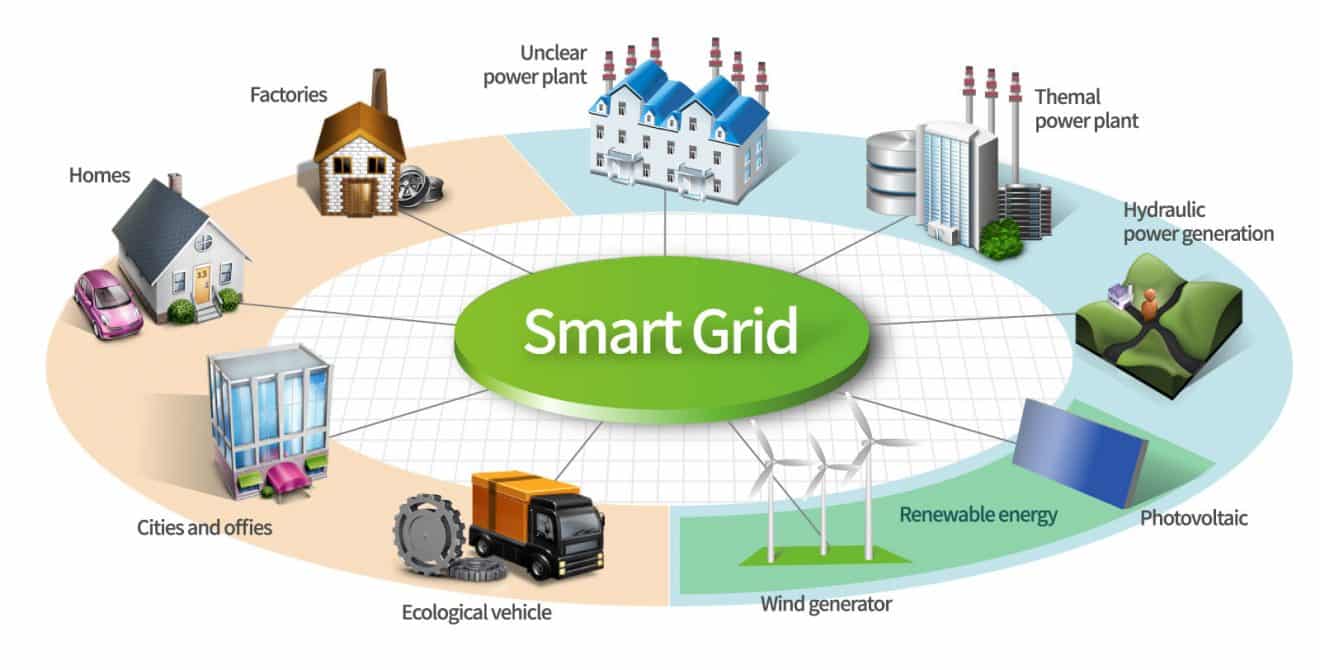

Technocracy and Technocrat bankers would drive all cash out of society in favor of a completely trackable digital system, which would give one more lever for social engineering. This is a global movement, not merely local, and resistance is building on several continents.