|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

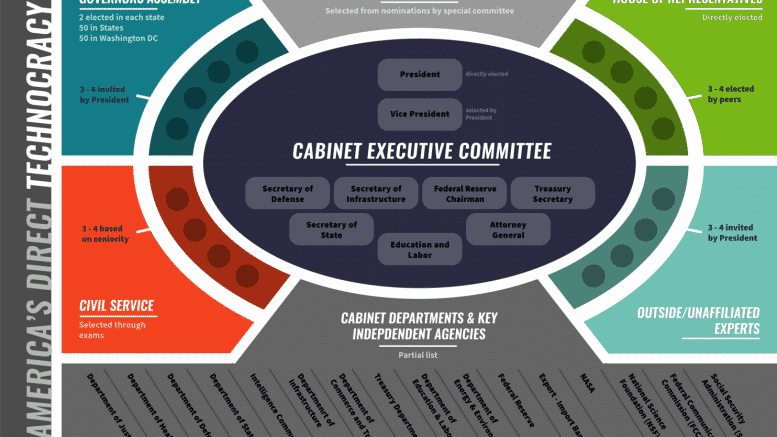

Parag Khanna's book, Technocracy in America, would turn the nation upside down, but he misrepresents Technocracy as some kind of benevolent partnership between democracy and civil experts.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Parag Khanna's book, Technocracy in America, would turn the nation upside down, but he misrepresents Technocracy as some kind of benevolent partnership between democracy and civil experts.